Children's books

Shimon wrote five children’s books in Hebrew between 1964 and 1967: Two Chicks and a Worm (1964), Titus, Come Home (1966), Tusbarahindi the Hero (1967), The Maharaja’s Ring (1965) and The Mystery of the Disappearing Border (1966), all published by Am Oved. The first three are for young children and the last two, for eight to ten year olds. There is also an unpublished manuscript, of an illustrated book written in English, which he gave as a gift to his grandson on his sixth birthday. Between 1952 and 1967 he was commissioned by Am Oved to illustrate six children’s books, by Shabtay Tevet, Ravnitzki, Van Abkoude, Dvora Omer and Chukovsky.

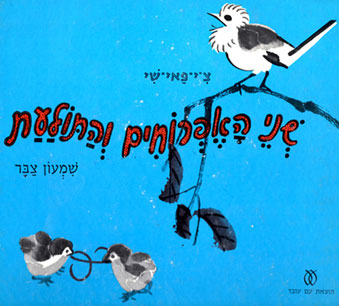

Two chicks and a worm (Am Oved, 1964)

In this book Shimon used the drawings of the Chinese painter Chi Pai-shih (or Qi Bai-shi, who was born in the Hunan region in middle China in 1863 and died in 1957), whose favourite themes for his pictures were birds, small animals, and flowers. Two Chicks and a Worm is a book with a selection of these paintings and of Shimon’s story in rhymes that accompany them. The result is a skilfully designed book with beautiful pictures and a simple story.

Titus come home (Am Oved, 1966)

Titus is the son of Rembrandt and Saskia, his wife, and the story, written by Shimon, is about Titus’ life as a little boy, closely follows the themes of a selection of drawings, prints and watercolours by Rembrandt reproduced in the book. This is an intelligent book that playfully introduces young children to some great works of art. This, and Two Chicks and a Worm, were part of a plan to publish a series of books for young children about art. There is evidence in Shimon’s archive of preparations for a book about Henri Rousseau.

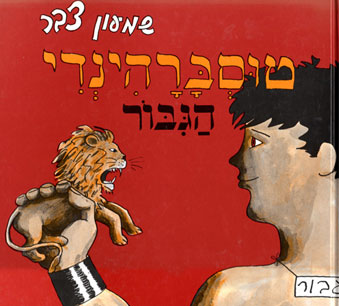

Tusbarahindi, the hero (Am Oved, 1967)

Tusbarahindi the Hero is the best known and loved children’s book by Shimon. It belongs to those few books read in childhood that are nostalgically remembered later in life, and which we want to read to our own children. The book had excellent reviews at the time, and is regarded by nursery school teachers in Israel as one of the best children’s books written in Hebrew, comparable in quality to the illustrated books of Nachum Gutman. Interestingly, when there was an attempt to find a publisher for an English translation of the book in the 1990s, it was rejected for being “too violent”.

The book is about Tusbarahindi who lived in Chumbalaya, and who, in his endeavour to become the next king of his country, had to go through a series of trials. First he was thrown into a very deep hole, a hole that was made by joining two of the deepest holes in Chumbalaya. He managed to escape from the hole, not by climbing out, which he could not do, but by shaking the walls of the hole with the strength of his body until they collapsed, and by simply crawling out. The second trial did not work: they wanted to push him into a very large saucepan of boiling water. The trouble was that no saucepan large enough to contain both the water and Tusbarahindi could be found in Chumbalaya: when a saucepan was filled with water, there was no room for Tusbarahindi, and when a saucepan was filled with Tusbarahindi, there was no room for the water. The third trial involved the creation of an even deeper hole than the first one by joining all holes in Chumbalaya, and importing others from abroad. Into this hole they pushed Tusbarahindi together with seven very big and very hungry lions. Needless to say, Tusbarahindi managed to stay alive and free himself. At this point he was given his last assignment, to find a princess to marry, before he could become the king of Chumbalaya. After a very long and tiring journey across land and sea, Tusbarahindi met Smarinuma, a beautiful princess, who, of course, was delighted to marry him. A child was born, who agreed to eat his porridge only if the story of his father’s adventures was told to him again and again.

The book is richly illustrated by Shimon’s drawings, which are magical and realistic at the same time. One of the reviewers of the book pointed out that the drawings were not simple illustrations that accompany the story; rather, it is a book in which the words and drawings are integrally belong together.

Tusbarahindi the Hero was first published in 1967 by Am Oved, and was re-issued in 1992. The reviews of the new edition were nostalgic and full of superlatives: “this is a wonderful book, simply wonderful” “it deserves to be a cult book”, “put it on the bookshelf next to Winnie the Poo” , “Rush to the bookshop to buy Tusbarahindi the hero, glance into it before buying, and if you are not enchanted, go to see a psychologist”. Some reviewers also bring up the biography of the book’s writer, and express their sorrow about his disappearance from Israeli culture, but emphasize that his life (i.e. his political views) and Tusbarahindi the Hero should not be seen as related. Michael B [H], in his obituary for Shimon, saw it differently.

This is reminiscent of what had happened in 1968, when Shlomo Grodzenski, in response to Shimon’s protest against the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, and the publication of Israel Imperial News in London, suggested in his column in Davvar that Am Oved should tear up Tzabar’s recently published Tusbarahindi the Hero, and sell the pages for packaging. The publisher’s response was even more interesting: “First we need to point out that the book was published in December 1967 when we had no idea that Shimon Tzabar was going to carry out his miserable activities in London. The book is an ordinary children’s book without any hint of Shimon Tzabar’s political activities. The review that was published in Davvar (19 February 1968) said that this is one of the best books for children recently published. Everybody should read this book’… There is no need to say that we are sorry from the bottom of our hearts about Shimon Tzabar’s destructive activities in London, but we will not carry out the public burning of his books" (Davvar, 28 March 1968).

The Maharaja's ring (Am Oved, 1965)

This is a book about the adventures of an Israeli boy who was selected to star in an Indian film, in India. The factual knowledge about this huge country, the atmosphere and the descriptions are based on Shimon’s own experiences in India.

The mystery of the disappearing border (Am Oved, 1966)

The book is about a boy, Ksirksil Tindle, with an amazing IQ of 247 who lands in Toledo, Spain right from the planet Avrak. He meets a group of children out for an adventure, and they manage to break the communication barrier between them by speaking in algebraic and geometric equations, rather than Spanish (possibly, a reflection on Shimon’s lifelong interest in mathematics). Ksirksil Tindle is enlisted by the Spanish government to solve the country’s problems that the grown ups could not, though he prefers doing the homework of his newly found friends. In the end, together with his friends, he manages to resolve a major security problem of the country: he wins over the enemy across the border by simply bringing about the disappearance of the border. One can see in his article for the Hadashot daily (Peace Now is Not Enough) [H] that this solution was not invented only for the sake of a happy ending of an adventure book.

The journey of the balloons to the end of the universe

This is an unpublished manuscript in English about all the balloons that managed to escape from the hands of their owners and fly into space. The manuscript was given by Shimon to his grandson.

The illustrated books (published by Dvir, Ha'aretz and Am Oved, 1952, 1954, 1955, 1965, 1966, 1967)

The illustrations in these books are in black and white, executed in different styles and techniques. The exception is Chukovsky’s book (Doctor Aybolit, a Russian version of Doctor Dolittle). The book was translated by Natan Alterman as Limpopo, and is stylishly illustrated by Shimon, perfectly matching the quality of the original writing and of the translation.